Text and Photos by Jason Buensalido , As seen in Urban Monologues, Business Mirror Newspaper (2007)

“Jorn Utzon, the architect of the Sydney Opera House, has never seen his masterpiece in the flesh since he left Australia in 1966.” said our animated tour guide. As if the design of the structure wasn’t interesting enough, I found out that the history of the building’s construction was even more colourful.

I recently took a trip to Australia where I felt like I was on another architectural pilgrimage. Any architect you talk to knows what the Sydney Opera House is, so it would be a shame if I didn’t see it with my own eyes. When I did, I didn’t realize that my jaw was dropped because the sight of the magnificent structure. It moved e, causing me to just stop and gaze in awe.

The idea of having an opera house in Sydney formed in the 940s, when a world-class visiting conductor came to the city to do a performance. He was able to talk to the city officials and told them that if they wanted to be a serious metropolitan, they needed to have a place where culture can flourish; they needed an opera house.

The visiting conductor probably hit an insecure nerve among the city politicians because after he left, they organized an international competition for the design of the Sydney Opera House. It was a very prestigious and high-profile competition, as over 200 entries were submitted from all over the world.

The entry of Jorn Utzon was already thrown in the trash can. Majority of the judges said that it was too different and too bold to be the new face of Sydney. Luckily, there was one judge who came in late and saw the entry in the can. He picked it up, spread it out, and showed it to once again to the other judges – “This should be our winner PRECISELY because it is different!”. Jorn Utzon, an unknown Danish architect, won 5000 dollars and the commission of the project. He moved his entire family to Australia and set up an architectural office there to oversee the construction of his work.

Originally, the budget for the opera house was 7-millon and the timeframe for construction was 7-years. What happened was it took 14 years to build, and about 102-million, which is about 1.2 billion today.

Naturally, the people of Sydney reacted during the course of construction. They started complaining that their tax money was being spent unnecessarily to build an opera house that they didn’t need in the first place. “We’re laid back people. We’re a country who loves the outback! We don’t need no opera house !”, I can almost imagine them say back in the 50s. The officials, since they wouldn’t take he blame themselves, they blamed the architect, Jorn Utzon. They tried to take him out of the picture and cut him out from the team to the point that he wasn’t being paid his salary anymore. Finally, in 1966, Jorn packed his bags and went back to Denmark with his family, giving up the fight for his masterpiece.

When he did, an Australian architect was asked to take his place. The Australians didn’t know anything about designing opera houses, so they were sent around the world for three years to study the design of different opera houses. They finished the opera house on October 20, 1973 and was opened by no less than Queen Elizabeth herself.

The design of the building is very interesting as well. When Jorn Utzon was conceptualizing for the competition, nothing was coming into his mind. Luckily one morning, he was simply peeling an orange when he realized that the forms of his design could actually be derived from his breakfast! He then cut different triangular shapes from the orange’s sphere and put it together to come up with the final design of the opera house, calling it his ‘spherical solution’. Maybe architects should eat while designing too. You’ll never where you might get inspiration from.

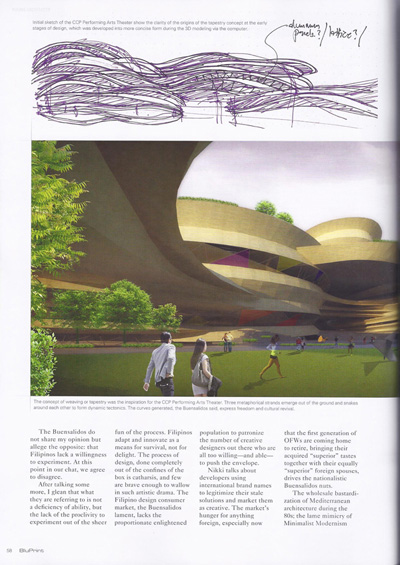

The design of the Sydney Opera House was derived from triangular sections of a sphere. The architect was eating an orange one morning when he suddenly thought of a ‘spherical solution’.

The Sydney Opera house is consisted of three sail-like structures sitting on a podium. The smallest structure is a restaurant, and then the two are performance halls. The sails have a very modern sculptural quality and it makes you wonder how they were able to put together a structure as complicated as that way before computers. The sails are made of pre-cast panels held together by tension rods throughout the hollow portions of the structure. They say that the opera house has more steel than the Sydney Harbour Bridge nearby. The structure was actually put together like LEGO, the famous toy product which incidentally is from Denmark as well.

One would think that the exterior of the performance halls were purely white. But upon closer inspection, I found out that it is finished with tiles with 3 shades – off-white, cream, and beige. This makes sense because if it were too white, the structure would be too glaring. The tiles are triple glazed, which made the opera house one of the first self cleaning buildings in the world. The dirt from its surfaces simply creeps down to the drains whenever it rains. Meant to look like giant fish scales, Utzon got his inspiration form Moroccan buildings which are usually clad with tiles.

The surfaces of the opera house are clad with tiles of 3 shades – off-white, cream, and beige. The tiles are triple glazed, which made the opera house one of the first self cleaning buildings in the world. Meant to look like giant fish scales, Utzon got his inspiration form Moroccan buildings which are usually clad with tiles.

The first among the two performance halls is fondly called the black theatre because of its interiors, and is the smaller one between the two. It is an opera and a ballet theatre, with a backstage that can be lowered two levels down. That is where the sets are changed, since the space on the stage level is too small. In reality, there are a lot of flaws in the black theatre, and that is why it is due for a renovation soon, with a budget of 500 million.

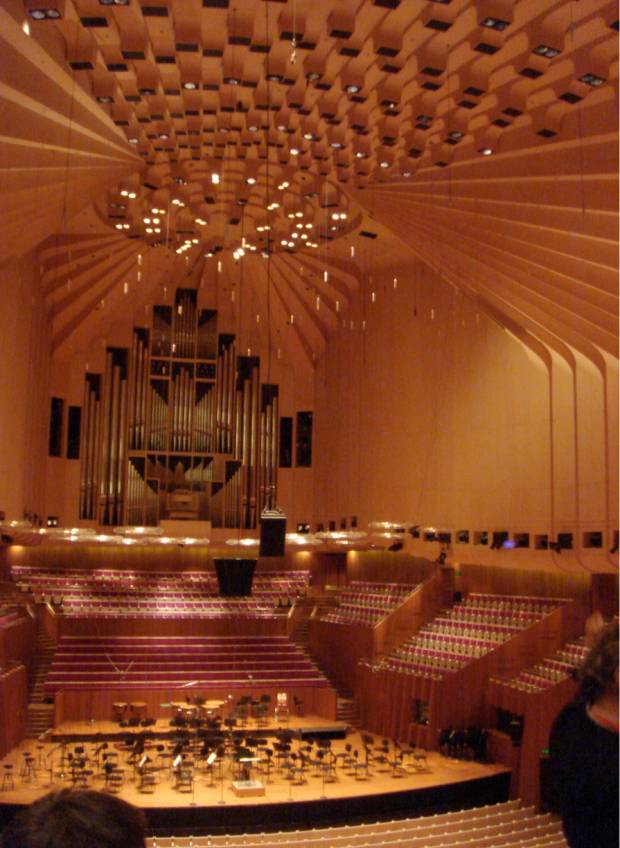

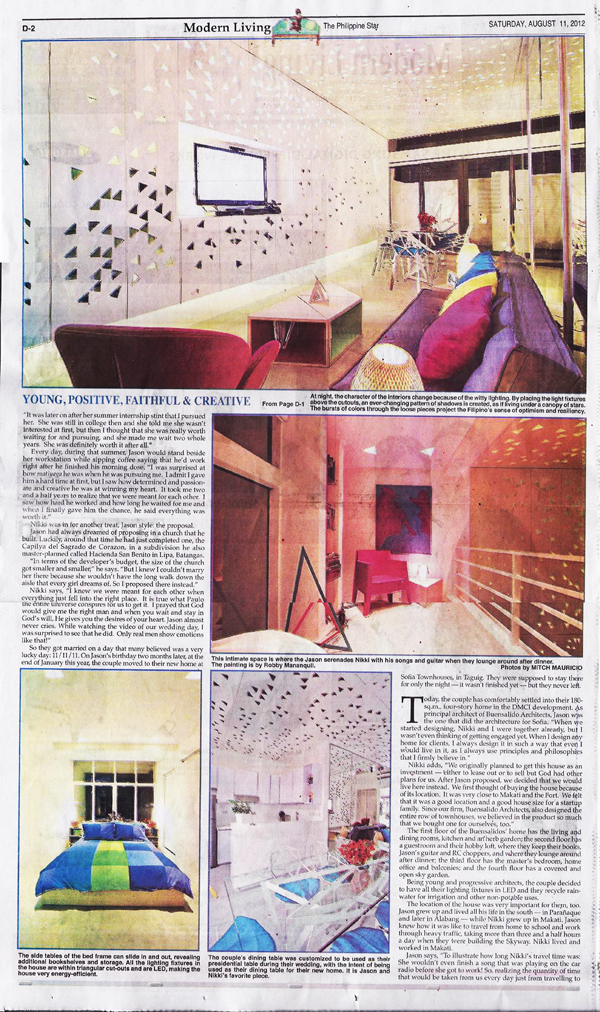

Then we proceeded to the bigger performance hall. I thought that I had my share of awe that day, but I was further moved by the design of the interiors of the second hall. It had a soaring ceiling with a shape that seems to spring from the ground, changing and morphing into different configurations as it goes up. Unlike the other theatre, this one doesn’t have a proscenium. There are seats even at the back of the stage. There is no need for microphones during performances at this theatre because the combination of hardwood and softwood used for the interiors bounce all the sound coming from the stage back to the audience. The organ is equally impressive. It is the biggest mechanical organ in the world. It has about 140 pipes, took 10 years to build, 2 years to tune, and cost about 3 million dollars.

The three sail-like structures sit on a podium. Utzon got his inspiration form a typical Mayan temple, where you climb up a long set of stairs to get transported into a different world. In the same manner, going up the stairs of the podium was meant to symbolize your transportation to a world of art and culture, leaving the stresses of urban life behind. The heaviness of the podium also complements the lightness of the sails. This is where all the service spaces such as the practice stages and studios are housed.

The interiors of the big performance hall had a soaring ceiling with a shape that seems to spring from the ground, changing and morphing into different configurations as it goes up. The author fulfilling one of his architectural pilgrimages

I guess every high-profile structure has its own story. The Eiffel tower and the triangular entrance the Louvre was loathed by Parisians. The Statue of Liberty was rejected by the Americans when it first arrived. The Guggenheim Museums, both in New York and Bilbao, received endless negative criticisms. Now, all these structures are weaved seamlessly into their respective cities. They now stand as the foremost symbol for the people that once rejected them, just like the Sydney Opera House.