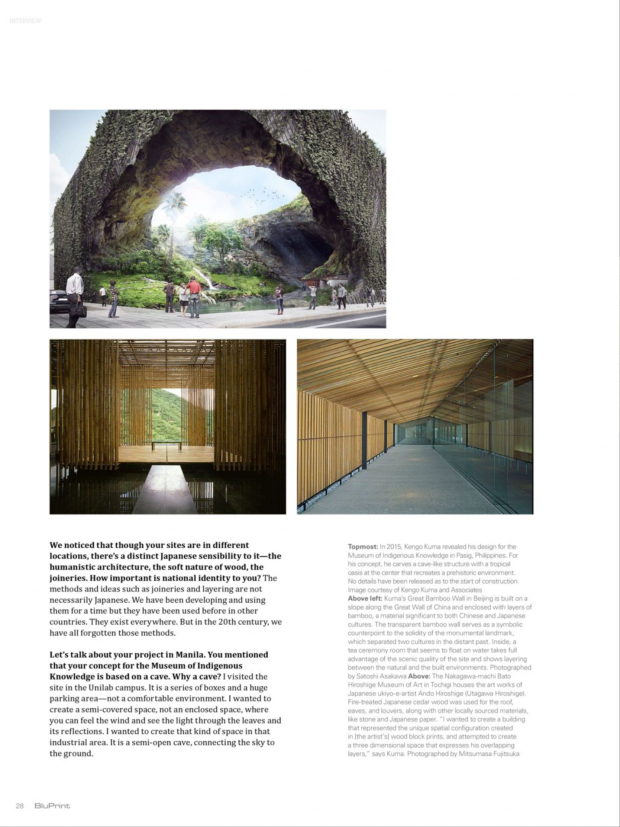

As written for and seen in BluPrint Magazine – July 2016. Interview held during Archinet’s 8th National Architecture Symposium held in April 2016.

Being familiar with Kengo Kuma’s work prior to meeting him, I have had a high level of respect for the level of authenticity in his architecture. His structures disseminate a message of material honesty, often leaving the chosen material for a specific project unadorned and in it’s natural state. The level of detailing shown in his work is distinctly Japanese, though the uniqueness of how traditional skills and natural materials are put together clearly is a manifestation of contemporary mechanisms and thought processes.

Sitting down with the unassuming yet physically towering icon of architecture and design, he revealed an even deeper part of his belief system and the stories that led him to form them.

I discovered that he is a man with many ironies – his buildings appear complex and contemporary yet the details and construction methodology are simple, scientific, and highly logical. His output seem like an end product of a process of advanced and digital architecture, yet he works in a surprisingly low-tech way, always relying on his sense of touch and intuition on choosing materials and discussions with his teams.

I discovered that his evolution as a designer was largely due to issues outside of his control. He was forced to go to Japan’s provinces and learn the traditional and local ways of building due to his inability to get projects in the industrialized urbanity of Tokyo. He shifted his mindset (along with a lot of Japanese designers) from the hard qualities of modernist ideals of design to the softer qualities of traditional architecture as a response to the failure of a host of concrete buildings during a massive earthquake in Japan. These situations were uncontrollable, forcing him to find other means of survival which I am sure he did not feel was ideal at that time, but actually led to the formation of his design sensibilities that brought him to the success that he is enjoying today.

I now understand that his aims in architecture are simple. He sees his buildings as filters, as screens, thru which we experience nature. He also wants to humanize the sometimes imposing and artifical nature of architecture (since it is after all, man made). Thru these, he hopes to achieve balance between man, nature, and architecture.

Interview Proper:

Ar. Jason: What’s the story behind you picking architecture as a profession?

Ar. Kuma: In the beginning, at the age of 10, the Tokyo Olympics happened. It was 1964, and my father brought me to the national gymnasium by Kenzo Tange. It a beautiful building and I was so shocked then. Aaaaaahh, I’ve never seen that kind of building . That was the first time to know the profession. Before that I wanted to become a veterinarian. I love cats. (laughs)

Ar. Jason: You love cats! You have cats now I assume?

Ar. Kuma: I have no time! But I was living with cats. But after that, from cats to concrete, from concrete to wood, which is the theme of the recent practice.

Ar. Jason: Being an architect, I know how challenging it can be. Our profession can cause a lot of stress. So how do you balance your life? Balance your time?

Ar. Kuma: If I would do the project by myself, it would stressful. But we are always making a good team and we are always discussing in the team. And we are always discussing cities, people, etc. And those kinds of dialogue are very good for stress, to avoid stress. And also traveling! Traveling is very good to avoid stress.

Ar. Jason: You mean traveling without work?

Ar. Kuma: No, for work! But after work we can drink. That kind of relaxed time is very important. In Tokyo, to find that kind of relaxing time is not easy. After dinner I would go back to office to have a meeting, meeting, meeting. Usually in Tokyo I would stay in the office until at least midnight. Normally, that’s how I work. It is very tough. But if I’m traveling, after drinking I can go back to the hotel and that’s why I prefer to travel.

Judith: Do you have time to relax in this trip?

Ar. Kuma: In this trip? Yesterday, old Japanese friends came here.

Ar. Jason: Well, maybe we can talk about running your practice. From what I know, you have a practice in Japan, you have an office in Paris. So first is, how do you divide your time, and how do you distribute yourself among these different office locations?

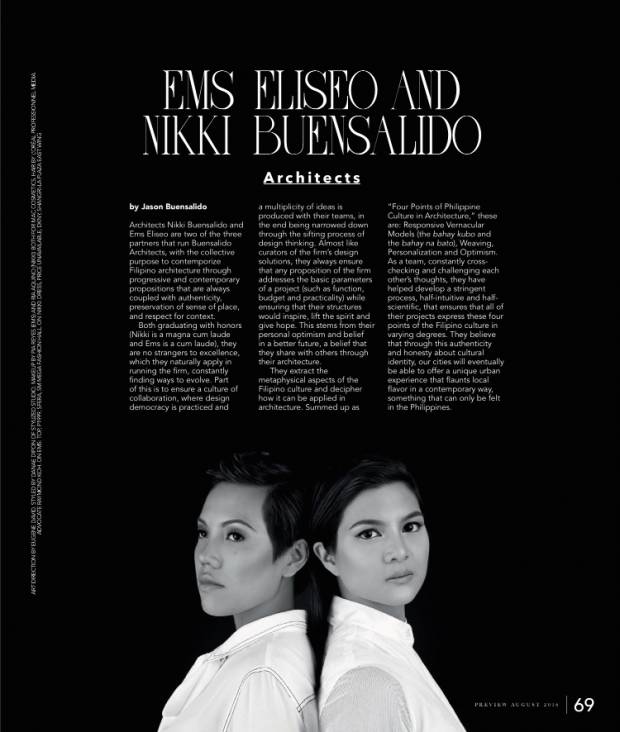

Ar. Kuma: Basically, once a month I go to Europe. I go to the Paris office, and then to U.K, Italy. What I do is I combine those trips once a month. And then I go to China once a month. For example, tomorrow I go to Beijing, then Xiamen and to Shanghai. Three cities in three days. And every month I go to those offices to have a direct conversation in front of physical model. It is very important for me. I don’t trust the 3d rendering. Rendering is 2d. The physical model is a reality. The materiality! I go there once a month.

Ar. Jason: Could you perhaps describe a typical project flow? For example, when clients in, how do you start the design process? How do you move on to the design development to construction until project delivery?

Ar. Kuma: Usually, first, I go to visit the site. I check the landscape and the flow of people. Always, we starts with the site visit. After the site visit, we make a physical model of the place – the mountains, the rivers, that kind of surroundings. That model gives me many hints about the place. And after that we have some discussions and stimulating each other. I didn’t want to start from myself. I’m only one of the members of the team. Everybody can say something about the project. And through those processes, we can go to the next step. And step by step, we have that kind of team meeting, in front of the physical model, and step by step we can go.

Ar. Jason: Okay, so do you still go to the site meetings, site constructions, site inspections?

Ar. Kuma: If the construction has started, I go to the site to check some material on the site. To check the material in Tokyo is not good because natural light is difficult, it’s different. Philippine natural light is so strong; the material looks different. The critical meeting, the critical material selection, and it should happen on the site. That is our policy.

Judith: So you do that for all your projects all over the world?

Ar. Kuma: Yes! Basically all the projects. Because for every project, the critical meeting does not happen every week. And also we can combine the site visits. One day in Beijing, or two projects in one day. We can combine the site visit.

Ar. Jason: So it’s just time management.

Ar. Kuma: Yes! And it’s still possible to check on site.

Ar. Jason: Can I ask something about what other writers call your “Architecture of Kindness” which you would champion? Because correct me if I’m wrong, that in the 80’s

there was a “Strong Architecture” in Japan. Most architecture then were based on industrialization and that’s when you went to the different parts of Japan and studied a “Soft Architecture”, to a certain extent, an “Architecture of Kindness”. So what made you shift from the concrete, purist boxes that time that were developing in Japan to this very humanistic kind of architecture that you produce now?

Ar. Kuma: A big change happened in the 1990’s. The 1990’s, economically, was a time of recession. I couldn’t find projects in Tokyo. In the 90’s , in ten years, I didn’t do any project in Tokyo. I traveled to the country side. I could only find small projects in the country side. But we had enough time to communicate with craftsmen. And enough time to find local materials. That was the period that changed Japan very much. And also in that period, we had some disaster. Before the tsunami, in 1995 was the Hanshin disaster, the Hanshin Earthquake, that changed the mentality of Japan. The big concrete buildings were destroyed and we began to think about “strongness”. That concrete and steel were actually very weak and the link of the community is much stronger than the “strongness” of concrete. That was the finding in 1990’s.

Ar. Jason: That’s when everybody shifted! I also read somewhere that you always start with materiality before starting with the design rather than starting with the design and then thinking of the materials after, is this true and was is the thought process behind this?

Ar. Kuma: The uniqueness of architecture is the material. Now, we have the internet. The visual image – we can get it very easy. But a visual image is just a shade, a color, but no materiality. Architecture is here - we can touch and we can smell and has weight. And that is the real uniqueness of architecture. After the IT revolution, probably 1990’s is when the IT revolution, the Internet revolution happened, people again found architecture realistic, more touch, more tangible. That was the new finding of the people. And then after that, my thought is going to that direction.

Ar. Jason: If you notice, we’re sort of suffering the same condition of architecture here in Manila wherein we’re surrounded with all of these concrete boxes devoid of context and devoid of culture. And I see that in all your projects you always bring out the sense of place. It’s very specific to the place. So context is very important to you.

Ar. Kuma: Yes! Every project, I’m go to the site and I ask the people to show me something old, , historical, the streets. For the Manila project, they showed me a prehistoric house, in a museum!

Ar. Jason: Which museum was this? National museum? Probably the Ayala museum?

Ar. Kuma: In the courtyard, there’s a house with thatch, floating floors, thatch roofing – very similar to Japanese. Aaaahhh, this is the same! And that experience gave me many hints.

Ar. Jason: We call it the bahay kubo. I noticed that after you choose the materiality, I always see a particular rhythmic, repetitive pattern in your projects.

Ar. Kuma: Yeah, yeah, yeah! That kind of rhythmic pattern is not an artificial pattern. We try to find some rhythm nature, from the environment. Because the environment always has some rhythm. And we try to translate those rhythms to architecture. And we try to avoid structure. In 20th century, people would like to show structure, to expose structure – from beam, wall, cable, or something. That is a representation of industrialization. But now we already left industrialization. We are living in a new period. And in this new period, that kind of rhythm is necessary for our life.

Ar. Jason: Yes, that’s why we need a humanistic kind of architecture, right? I learned in your talk that one of the features of your design is layering between the user and nature. What’s the reasoning behind this?

Ar. Kuma: Life needs layering. We have those kinds of layers to control the relationship between the body and the environment. Animals also creating their nest by layering. Layering is a basic method of life and we just translate that method to architectural design.

Ar. Jason: I have few more questions; I hope you can bear with me a little bit. We’re just grabbing this opportunity because this is a privilege for us to be with you. We noticed that though your sites are in different locations, there’s a distinct Japanese sensibility to it. The joineries, the humanistic kind of architecture, the soft nature of wood. How important to you is national identity?

Ar. Kuma: That kind of method, for example the joineries, the layering, is not necessarily Japanese. In Japan, we are have been developing that method for a time. But everywhere that kind of method has been happening before. But in the 20th century, we have all forgotten those methods. And I don’t want to stick to Japan. It is not Japanese. Everywhere, it was existing.

Ar. Jason: I have a question about your project here in Manila. You’ve mentioned that it’s based on a cave. Why did you choose a cave for the origin of the design process?

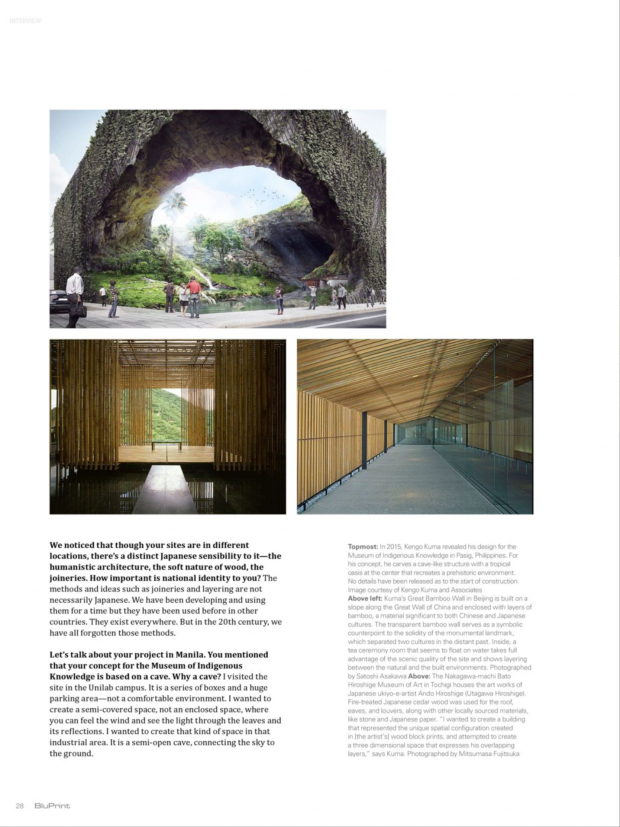

Ar. Kuma: I visited the site of the project – the Unilab campus. It is a series of boxes and parking – not a comfortable environment! I wanted to create some semi-covered space, not an enclosed space; a semi-covered space where you can feel wind, light, light with reflection, light thru leaves. I want to create that kind of space in that kind of industrial area. It is not an enclosed cave, it is a semi open cave. It is connecting the sky and the ground and the goal of this design is to achieve that kind of quality of space.

Ar. Jason: One last question. You know, Filipinos, we have a certain level of colonial mentality. We were colonized by different countries and so majority of Filipino architects, they’re not confident about developing their distinct voice, distinct sensibilities and reflect it in architecture. But you, obviously, have developed your own, your own language based on the site, your understanding of the site and you use architecture to basically flaunt the qualities of the site. So what can you say to us Filipino architects to gain confidence?

Ar. Kuma: In Japan we also have a big influence from China, and the Japanese language is very

much origined from Chinese character. We are still using Chinese character. Everywhere we have a history of cultural exchange. Colonialization is part of that cultural exchange. And cultural exchange is not bad for countries. Still, we want to do some exchange with other cultures. That kind of stimulation is good for our own culture. For the Philippines, as an advantage of the Philippines, you can have the chance to communicate with Spanish cultures, American cultures, and also you have a very interesting pre-historic cultures. You have many chance to communicate and you can utilize this chance and maximize the cultural exchange and develop uniqueness. Uniqueness can developed from cultural exchange. I expect that Philippine culture can achieve some unique, interesting things.

Ar. Jason: Words of wisdom!

Judith: One question. I think many many many people around the world will be studying you and studying all of your work, so I’m wondering, is there something about your work or about you that you would like people to learn from your example and is there something you think “Oh don’t copy this! Don’t copy this!”.

Ar. Kuma: No, no. To learn my detail and to learn how to use material is good. In the 20th century, identity is very important. – branding, identities. But now people are using other people’s idea. That kind of culture is creating something. This is our new method. “Please come to me” and “Please come to my architecture” if it is for developing your style.

Ar. Jason: The world is getting smaller. It’s all becoming just one single space. Cultural exchange is becoming a norm.

Ar. Kuma: Yes, one single village.

Ar. Jason: Cultural exchange is great! Thank you very much! Yoroshiku Onegaishimasu.

Ar. Kuma: Arigatou!

L-R - Jason Buensalido, Judith Torres (EIC of BluPrint), Kengo Kuma